Knocking on doors around Indiana as a field canvasser for the Citizens Action Coalition, Bryce Gustafson has seen the political division among citizens falls not so much between Republicans and Democrats as between urban and rural.

Residents of small towns and farm communities have a knee-jerk reaction to what they see on the local news, believing people in bigger cities such as Indianapolis are out of control, he has observed. Meanwhile, those living in larger metropolitan areas tend to look down their noses on folks who live in the countryside.

“I think it’s always been there to a certain degree,” Gustafson said. “But in my 10 years, I absolutely feel like the fabric of our civic life is kind of splitting apart in real time.”

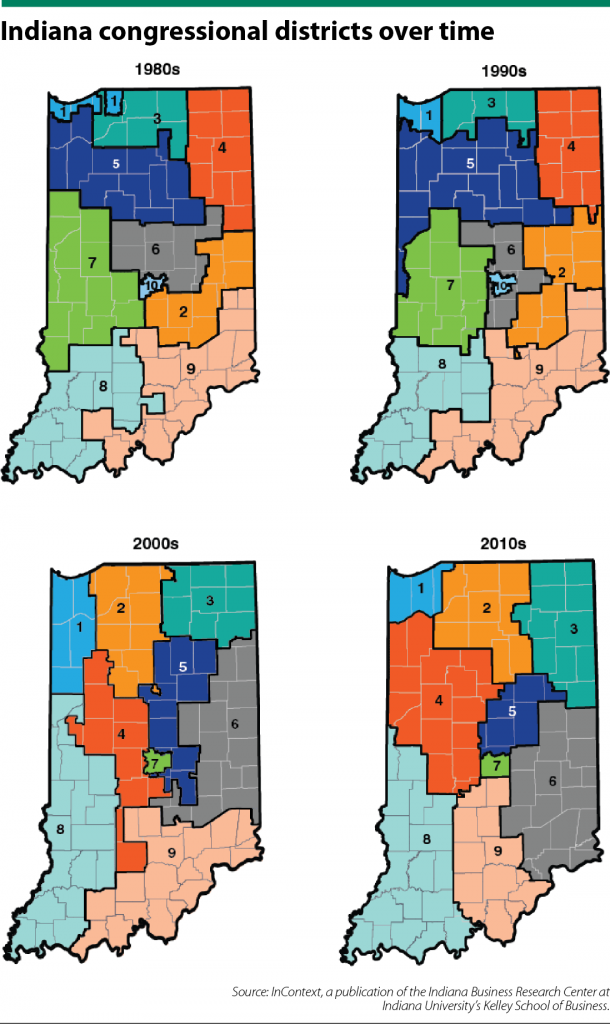

One way to stitch the Hoosier State back together is to quit gerrymandering, he said. Legislative and congressional districts have been drawn across Indiana so that slivers of urban areas are attached to large swaths of rural land. As a result, voters are not given true representation because their elected officials are representing segments of different communities of interest rather than a segment with common interests.

Vaughn

Vaughn

However, this year, the delay in compiling the U.S. census population count has presented Hoosiers with an opportunity to potentially impact the redistricting process or, at least, demand the legislators explain their reasoning for their choices.

The legislators typically create the new maps during the legislative session. Julia Vaughn, policy director of Common Cause Indiana, explained the process was harried and never very transparent as lawmakers juggled redistricting with hearing and debating a plethora of other bills.

Not surprisingly, the public had limited chances to be included in the process. Now, with the General Assembly planning to return in a few months to focus exclusively on redistricting, lawmakers have time to listen to their constituents.

“We have found a public that is more than engaged, more than interested in talking about the details of this,” Vaughn said, adding voters understand that “where the lines fall” determines who gets elected and which issues get attention. “A big lightbulb has gone off across our state and people understand redistricting really matters and they want to have their voices heard.”

Competing interests

Under the maps drawn in 2010, Hoosiers in rural parts of Indiana currently have an outsized role in the Legislature, according to Vaughn.

An example of this is Senate District 28. Along with encompassing large areas of Hancock and Shelby counties, the district has a tiny appendage extending into eastern Marion County. Vaughn said the district is difficult for Sen. Mike Crider, R-Greenfield, to represent because it includes “radically different communities of interests,” with the needs of the Indianapolis residents struggling to compete with the needs of farmers and small-town residents.

An example of this is Senate District 28. Along with encompassing large areas of Hancock and Shelby counties, the district has a tiny appendage extending into eastern Marion County. Vaughn said the district is difficult for Sen. Mike Crider, R-Greenfield, to represent because it includes “radically different communities of interests,” with the needs of the Indianapolis residents struggling to compete with the needs of farmers and small-town residents.

In preparation for this year’s redistricting, a coalition of grassroots organizations, including Common Cause and Citizens Action Coalition, have launched the initiative All IN for Democracy. This project is focused on bringing Hoosiers into the map-drawing process.

The All IN effort has hosted a series of virtual town hall meetings across the state where people could tune in and make comments and observations. Vaughn said in those meetings many Indiana residents echoed a common refrain that their voices are not heard and their elected officials do not respond to their letters or come to their community forums.

“We have people across our state who are struggling to be good citizens,” Vaughn said. “They show up and vote every election and they engage in organizations and they write and call their legislators and they feel like it falls on deaf ears.”

In the congressional district now represented by Republican Jackie Walorski, the rural and urban divide has become more pronounced as the maps have been redrawn.

It was the Third Congressional District at one time and hugged the Michigan state line. But it was renumbered as the Second Congressional District in 2000 and it has been stretched south and east. At present, the district includes the city of South Bend, with a population of 102,026, according to U.S. census data, and the counties of Marshall, Fulton and Miami, which have a combined population of 101,454.

Bennion

Bennion

An issue that highlights the divide between rural and urban interests is the environment, according to Elizabeth Bennion, professor of political science at Indiana University South Bend. Residents of the metropolitan area, for example, are concerned about pollution and confined animal feeding operations while farmers have concerns about regulations stifling their ability to grow food and make a living.

The impasse is reflected across the country where citizens with opposing views pick a side instead of coming together to talk and find areas of compromise, she said. This is placing more stress on congressional representatives because the populations in their districts are growing and they are having to represent more and more people who have very different needs.

“This is very tricky because as much as we say, ‘You are not the representative of the people who voted for you, you’re the representative of your entire district,’ there will be choices to make in terms of votes and also determining how to spend your time,” Bennion said. “So, it can be tempting for the representatives to spend the most time, energy and effort focused on the issues that matter to them most personally and the people most likely to return them to office.”

Fairness

Legislative leaders have not announced many details about the upcoming redistricting process. However, Senate President Rodric Bray, R-Martinsville, told The Indiana Citizen the public will have the opportunity to participate.

Likely by midsummer, lawmakers will start holding public hearings around the state so Hoosiers will be able to provide testimony and, when legislators return to the Statehouse, watch the map drawing as it progresses. Also, just as All IN is doing, the Legislature will be inviting the public to draw their own district maps.

Gustafson has found that Hoosiers, regardless of where they live or how they vote, understand the idea of fairness. He recalled an encounter with a man while canvasing in Franklin. The man was initially dismissive, telling Gustafson he liked the way things were. But when Gustafson pointed out the other side would be able to exert broad power if it gained control in state government, the man agreed that gerrymandering is problematic.

“Once you bring up the idea of fairness and process,” Gustafson said, “that’s when they say, ‘You’re right, that’s important to me.’”